McCarthy-Andersen joint venture pour foundation of KCRB

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, October 25, 2016

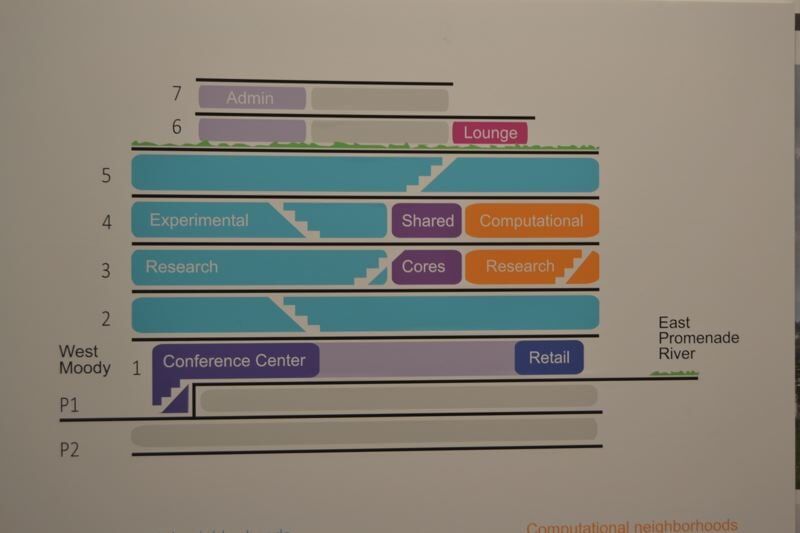

- Details of the build are pinned up on all the walls in the trailer, including this one of the overall floor plan.

The culture in the Knight Cancer Research Building’s co-location trailer is evolving as the development’s designs are fine-tuned and the focus shifts heavily to construction.

Trending

At the South Waterfront site, known for its innovations toward cancer research, to architecture and to workplace culture, builders poured the KCRB’s concrete foundation this week.

On a Tuesday morning at 9 a.m., everyone — interior designers, subcontractors, OHSU core team leaders, engineers and more — in the co-location stands up from their open-plan office desktops and faces a giant calendar along the wall from top to bottom, showing the pull plan for the entire development.

Quick updates come from every department: the masonry subcontract is out and signed, the steel subcontract is finalizing numbers, the electrical outlets and switch locations are done, the floor plan dimensions strategy is done, skylight and metal panel detailing are being worked on, a water meter vault may need adjusting according to PBOT, engineers are updating electrical drawings and the elevator core is in place.

Trending

Fewer than thirty minutes later, 40 people are all caught up on the $200 million development’s progress that week, and start to talk in break-out groups. It happens organically, a byproduct of the collaborative environment. Some days, up to 70 people attend.

Architects, developers and contractors are rolling the KCRB forward all at once. “Go slow to go fast” is the motto, meaning wait for other departments to catch up and troubleshoot as each part of the building comes together.

The mechanical engineer

Jeff Slinger, mechanical engineer with Andersen Construction, makes his job at the co-location sound like Christmas in a utopia.

“This project has changed my outlook on my whole career and also changed my personal life,” Slinger said. “The way construction normally works, there’s a lot of adversarial relationships because contractors have to put the lowest possible number together (for bids) … it puts the contractor and owner in an adversarial relationship.”

Between contractors pricing competitive bids for developments and still keeping food on the table, knowing owners want to keep its costs low and architects want to keep it looking fancy, Slinger grew tired of the pain of the push-and-pull.

“In this scenario (at the KCRB) where everybody gets to work together, I get to be friends with everybody and we get to tell everybody the truth and we get to work together and it is so refreshing,” Slinger said. “It’s like taking everything you hate about your job and throwing it out the window and just not doing it, and just doing the things you love about it. It’s given me a whole new outlook.”

Now, sitting in a trailer with OHSU core team leaders alongside his mechanical contractors, Slinger has the freedom to reallocate tasks based on team members’ strengths, not job titles.

“This is really a great scenario: What does the mechanical engineer do and what does the mechanical contractor do? It’s not clearly defined,” Slinger said. “Invariably, (usually) things are put in one’s box that he’s not very good at but he has to do it because it’s in his box. In this scenario, we can talk about what’s in your box, who’s the right person to do it, and structure a person’s box to all their strengths.”

The difference for contractors in being at the co-location is much larger than it is for the architects, who still have their desks, computers and meetings. Contractors usually have their own on-site trailer with drawings — that aren’t being constantly updated — simply ready to build one step at a time.

“It’s the small things, but having a shower here is a really big deal,” Slinger said. “My whole career I work in a trailer. It’s a trailer in a gravel parking lot full of mud, a miserable spot usually. But this — we’ve got a patio, a BBQ, a river view, a shower, I can rent an orange bike all over the place if I just need to clear my head.”

Along with pizza lunches, potlucks and BBQs, the co-location put together a Hood to Coast team, and runners go out together at lunchtime or after work.

“We have a book club! I’ve never even been part of a book club, but now I am,” Slinger said. “Part of me is panicking — this job is going to end, I might be spoiled.”

“Am I ever going to be able to go back to that adversary? I don’t think I can. Once you experience really awesome teams, all the joy and none of the pain, I don’t want to go back to the way it is,” Slinger said. “That makes me panic at night, but is a testament to how awesome this project is, to be able to work in what looks like a third grade classroom — I got sticky notes and I got all my friends and we have a lunchroom, we’re having pizza day tomorrow, how awesome is that. The only thing missing is recess and tether balls.”

The director of design management: bridging architects and engineers

Stefanie Becker, director of design management with McCarthy Building Companies on the joint venture, used to be an associate partner with ZGF Architects. In her role here, she helps bridge the communication between architects still collecting data and contractors anxious to have plans in order to build.

“The cultural difference between the designers and engineer-type builders who are very linear, they want decisions and then you move on, and decide, and move on, where designers are bringing in a lot of information and it’s constantly happening,” Becker said. “It’s a big challenge to learn to respect those different approaches, but you’ll still get people frustrated with each other because that’s not normal. Some people think it should go in order.”

In the co-working location, there are strategies to shield against the friction: a personality wall showing in-depth types hangs in the trailer, and round red Elmo (standing for “enough, let’s move on”) balls are thrown in meetings to keep them short and sweet, and to keep individual problem-solving to personal time.

“We all come together to talk about what our teams are working on, and it’s the natural behavior of getting together: you heard somebody say something and you want to go coordinate with them,” Becker said. “Everybody wants to be respected and has different ways of hearing each other, receiving information, and I’m trying to be sure that’s happening across the board. We’re reaching a really critical point right now.”

The KCRB plans are split into three permit packages: deep foundation and structure up to the first floor, the rest of the structure up to the seventh, and finally everything inside. The split allowed construction to get started on the foundation while the rest of the design is still partially in production.

“People in here are starting to owe stuff to the field, there’s a lot of back and forth,” Stefanie said. “We’re very specific about when deadlines are so the architects don’t get overloaded with submittals.”

She said they had a “lessons learned” forum with OHSU for a few of its other upcoming projects to discuss what works so far in the KCRB co-location workplace culture strategy.

“This team has done a great job of realizing their differences and accepting that and still working to the end of the common goal of early cancer detection,” Stefanie said. “Instead of negating or competing with architects, but to collaborate with architects, I want to show how they both can work together well.”

McCarthy-Andersen joint venture project manager

Kyle Becker (no relation to Stefanie Becker), project manager with the McCarthy-Andersen joint venture, came from the McCarthy Building Companies side. He moved to Portland from Oakland, California in pursuit of the KCRB.

He’s a mechanical engineer with an electrical plumbing focus who has already moved to Washington, Denver and Omaha before Oakland for construction gigs. On the KCRB project, his job focuses on the structural side, “to get a little more rounded in my experience,” he said.

“A lot of times as the contractors, we kind of look back and question a lot of things the designers did — just having no idea what process they’re going through,” Becker said. “It’s eye-opening to understand the different steps — they do take everything into consideration.”

In February 2015, 15 months before the KCRB broke ground (June 2016), Becker was already working with the architects through the planning and permit packages, interjecting with concept studies and schematic drawings.

“The level of thought that went into the planning, it wasn’t just drawing labs and benches on paper and placing offices where somebody thought they best fit — there is a lot more background and optimal design,” Becker said. “A lot of this we never see: even from the concept of how the building works, understanding how they get the user input, go through the concept design to construction documents, has been really eye-opening to see why the designers make the decisions.”

Inside the co-working trailer, teams are set up in pods for functionality.

“Everybody, a mix of designers, trade partners, contractors and owner’s representatives, they all are focused on the structural components, mechanical, electrical, plumbing and interior located within those pods,” Becker said. “We had to make sure we’re thoughtful enough to get them co-mingled, but still have close enough proximity to the management focus of each individual company that we can maintain our company’s structure and oversight to what we’re doing.”

Becker said people are constantly coming in from the field to ask questions. The work right now is focused on structural components, whose team is located next to the interior design team, who are working on getting the interior design package ready for permit.

“Our structural detailer sitting directly across from an engineer, I would see them poking their heads around their monitors just bouncing ideas off each other trying to figure out the best way to pour the slabs,” Becker said. “Is it better to design two pours and do it in half? To pour the center core first, and then do the outer two sides? They were working through that, bouncing ideas off each other, and ended up going in the direction the way it would be for construction and the design modified for that.”

He said the designers tell them when they’re not going to be done, where they’re going to make changes, how much they can design based on what they know so far, and when they’ll get more feedback to learn more. On his side, contractors came in expecting the plan to be linear, going from one step to the next, each building on the last.

“It’ll spin forward and then come back a little, spin progress a little more and come back,” Becker said. “In the end, we’re going to get to the same results, it’s just the way, the process. It’s going to make everybody better at performing their jobs.”

The calendar pin-up that takes up the length of a long wall keeps all the departments on track and accountable.

“Something about writing that sticky note and putting it on the wall, that’s my commitment to the team,” Becker said. “Everybody who’s actually putting the work in place owns their own schedule making commitments to other team members and are able to hold each other accountable.”

jrogers@pamplinmedia.com

A DAY IN THE LIFE

This is the third installment in an ongoing series of stories about the people who are bringing the Knight Cancer Research Building from conception to reality.

The first article (Business Tribune, July 1, 2016) focused on two of the architects of the project.

The second (Aug. 19) focused on the OHSU core team members.

In this installment, reporter Jules Rogers spoke to contractors and engineers from the McCarthy-Andersen joint venture to showcase how a day on the KCRB co-location has its own workplace culture.

It was only a year ago that OHSU announced they had met the $500 million match required to secure a $500 million donation from Nike co-founder Phil Knight and his wife Penny.

Now, work has begun on the Knight Cancer Research Building, the construction of which is estimated to create 3,600 direct and another 4,400 indirect jobs.